In this situation, inexperienced traders can be easily influenced by their emotions, which can lead to bad decisions. For instance, the phenomenon known as “risk aversion” is a cognitive bias that leads the trader to avoid risking what is already secured, and this often results in situations where closing a position early leads to missing out on potential additional gains.

An experienced trader should have already overcome this emotional hurdle; however, in both cases, knowing the current deviation from the historical one can be a decisive indicator in our choice of the best moment to exit.

The aim, in this case, is to understand the deviation data (limits) in order to ascertain if historically there is still room to wait for additional profit, or, on the contrary, if one has already reached limits for which there is little historical probability to support the decision to keep the trade open.

Let’s imagine, therefore, that we are in this situation:

Given the current position, which is LONG, I am only interested in evaluating the potential upside. The goal in this case is to decide whether to take the money or let the trade continue. We bought APPLE stock when it was $125 per share and it is currently worth $142.50. Our unrealized profit is $17.50 per share, which is a 14% increase from our purchase price.

When we opened this trade, we did identify potential exit areas, but we decided to enter the market without a take-profit exit order, just a stop-loss, which was calculated based on our money management strategy. We also had an idea of how long we would need to stay in the market to reach our take profit target. We decided that the operation should last a maximum of one month.

The purpose of our analysis is to determine whether our current profit of 14% is within the expected range based on historical data. In simple terms, we need to understand how much this stock typically moves in a month (perhaps that month) and compare it with the current deviation to decide whether it has already yielded enough or if it can still generate additional profit.

Knowing that each filter yields a dataset of varying size and similarity to the current market conditions, we will begin a series of searches with the series filter aimed at gathering information to help us understand historical behavior. Since every filter applied changes the probabilities and the number of similar historical cases, it is important to conduct multiple research efforts and extrapolate a definitive “personal” figure by blending various analyses.

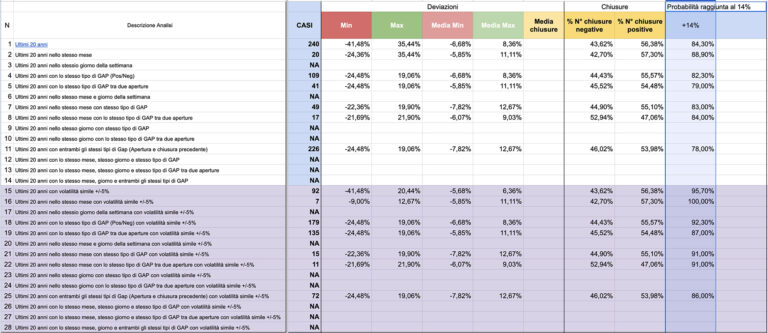

For each analysis, we will take a look and note down these values, as well as the number of records extracted from each search:

The MetricAlgo tool to be used in this case is the limit analysis found within the Historical Stats tool package. Select the APPLE stock from the Dashboard and enter the tool where we will start to set the filters to perform the analysis. The first thing to set is the timeframe, which in this case will be set to “monthly” and we recommend selecting only the last 20 years of the series.

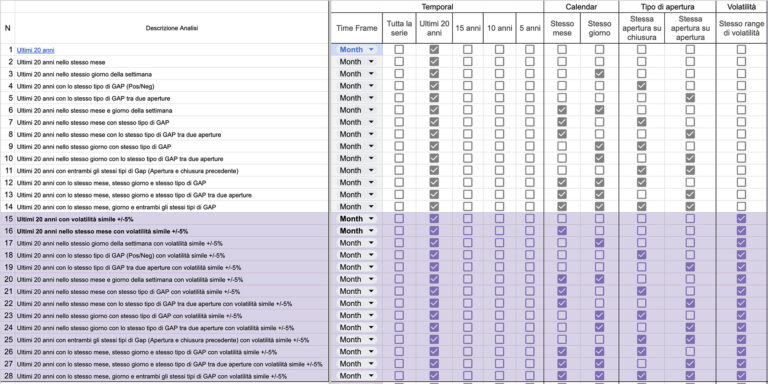

The various combinations of filters and the corresponding searches that we will carry out could be:

to which another set of identical analyses should be added, but with the addition of a volatility filter, for example in a range of +/-5% from the current volatility value. In this way, you can compare historical results with others more specific to the important context of “the same volatility. In this way, from the 8 previous analyses, we would obtain 16, including two sets that differ in terms of volatility. Here’s an example in the image:

It goes without saying that an analysis of the last 15 or 10 years will each yield another set of 28 results. Furthermore, it’s important to understand that choosing volatility as the final element of comparison is an arbitrary decision by the trader or historical data analyst, who can decide the order they prefer in their filtered investigation of the series.

Moreover, for completeness, it should be mentioned that some of these analyses do not make sense in specific timeframes; for instance, analyzing a monthly period while trying to filter by “day of the week” is not applicable.

Once all the analyses are completed, we can compare the data and immediately notice that the 14% deviation achieved by my trade is an exceptional event, as the averages of the highs are lower than my 14% (I am performing better than the historical average), even in the analyses where I do not take volatility into account for comparison.

Furthermore, it can be observed that a deviation of 14% in a month is achieved slightly more than once every five times (meaning there’s approximately an 80% chance that it won’t be reached, thus a 1 in 5 chance that it will be). Since I arbitrarily consider that in a monthly timeframe the gap between the opening on the first Monday of the month and the closing on the last Friday of the month is statistically insignificant, while the gap between the two openings indicates a precise trend, I have decided to use the four results and discard the others even though they more or less confirm the other results.

When we apply volatility, the data even suggests that with the current low volatility, reaching 14% is even more difficult, bringing the probability down to 1 in 10 from the previous 1 in 5. In one specific case, the 14% was actually never reached under those conditions, which once again indicates that the price has marked an important historical limit, and fortunately, we are in it.

After analyzing the data, starting from my bullish standpoint and understanding that in less than a week the stock has shown a record deviation, I can draw the following conclusions:

It follows that in this case, duly informed by the historical data, it is better to realize the profit, but we have left the option to continue to stay in the market if the momentum supports it because history does not predict; it calculates the past to give us data useful for our decisions.

The current reality can present exceptional individual deviations at any moment, and it is up to the trader to blend this information with the momentum. In this case, however, I would have closed because history tells me that I have already been fortunate to realize more than the average.

If the historical data had shown that there was a 30-40% chance that the price would continue to rise, then I would have decided to stay in the market. I would have been willing to take the risk of losing my unrealized profit in exchange for the possibility of making even more money.